Collateral re-use dropped off dramatically after the financial crisis of 2008, but has been recovering since 2016. FIS’ David Lewis explores the implications

It is rarely a good idea to use the same analogy twice, but where collateral chains are being discussed, the re-use of an analogy to illustrate a point seems more than appropriate. When describing the frenzy around scarce securities (in the prior case, the focus was more around short selling concentration on a few hot securities) the sight of my young son and his teammates traversing the rugby pitch like a frenzy of bees all tightly packed around the ball seemed fitting. There was little structure and the unnecessary competition created resulted in very poor outcomes for all those involved, including those watching.

While trying not to stretch the analogy to breaking point, the scarcity of the desired asset – in this case the ball – is somewhat representative of collateral in the global financial machine. Perhaps more specifically, it should be defined as acceptable collateral, as few would argue that there is an overall shortage of collateral on the markets. The level of availability will correlate directly with the counterparty’s specific definition of acceptability. Gone are the days when clients of a custodian’s lending programme formed a homogenous group accepting the standard collateral schedule set by their agent. Like many aspects of commercial life, clients are taking much greater interest and exerting much greater influence on the processes and strategies employed by their providers.

There are few areas where that effect is being more acutely felt than the rise of client expectations around environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles. The rise of the caring and environmentally conscious corporation has been astonishing to observe over recent years, with almost every organisation touting their care for their clients and the environment, and even offering services and support that appear, to the casual observer, to be beyond their core purpose. What does that really mean for the investment community and the wider financial industry, including securities lending and collateral management?

It has long been an accepted rule that no lending fund should accept a security as collateral that it would not be permitted to invest in directly. The purpose of collateral is to secure the lender’s ability to repurchase the lent security should the counterparty fail to return it, for whatever reason. While it would be rare for a securities lender to keep the collateral for any extended period instead of selling it quickly to recover the asset lent, it will become that investor’s property for that time. As such, it cannot be something the fund is not permitted to own.

The challenges such restrictions create have a multiplying effect when the investment objectives and rules of the fund, whether self-imposed or based on enforceable regulations, restrict the types of assets they can invest into a narrow or scarce band. As has been discussed in this publication at length, ESG-compliant assets are relatively few, although the definition of what constitutes an ESG-compliant asset can vary enormously. When the definition is too broad, there have been accusations of greenwashing thrown around the market, a suggestion that the application of policies may not be all that they seem. Where the definition is too narrow, the potential asset pool becomes very shallow.

With an evolving set of standards, there are always going to be different levels of interpretation and application. Enter the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). New articles for adoption into SFDR are in draft form only at present, but give a good view of what will be handed down by regulators when they come into force, potentially as early as January 2022. As currently drafted, they include terms that are certainly open to interpretation such as “promotes environmental or social characteristics” or the higher bar of “incorporate good governance into its investment strategy”.

How investment managers interpret these guidelines will impact the range of securities that they can invest in, hold as collateral and, of course, restrict from lending so that they can vote on key issues affecting the issuer’s green strategy, for example. Every time a restriction is applied, the field of choice is narrowed and this may impact the diversification of funds and their ability to outperform a given benchmark.

Collateral velocity

When considering the collateral management aspect, the situation may be even more complex. Collateral velocity is a key measure monitored by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and, in particular, the collateral expert Manmohan Singh. The length of collateral chains and the level of re-use give a direct indicator of international market liquidity. Increasing amounts of collateral are needed as more and more regulations demand collateral to back financial transactions, with a leaning toward collateral that is not already committed or sourced from outside the organisation.

The shorter the chain, arguably the easier the collateral asset is to recover and the more stable the underlying market. In 2008, chains became significantly shorter as those receiving the collateral shunned re-use and those pledging it feared that they would not get it back. This effectively reduced the availability of credit in the market. Collateral re-use had been estimated to be around three times prior to the financial crisis but dropped to less than two times up to 2016. At the end of 2020, when the last data on this was made available, velocity had recovered to 2.5 but remains stubbornly below pre-crisis levels. Availability of collateral, particularly high-quality assets that are pristine (i.e., not those at the end of a long chain of pledging and lending) may be challenged by debt issuance limits being set by the US Federal Reserve and others, together with asset purchase schemes that remain in force. Does this mean the market might be facing a collateral squeeze?

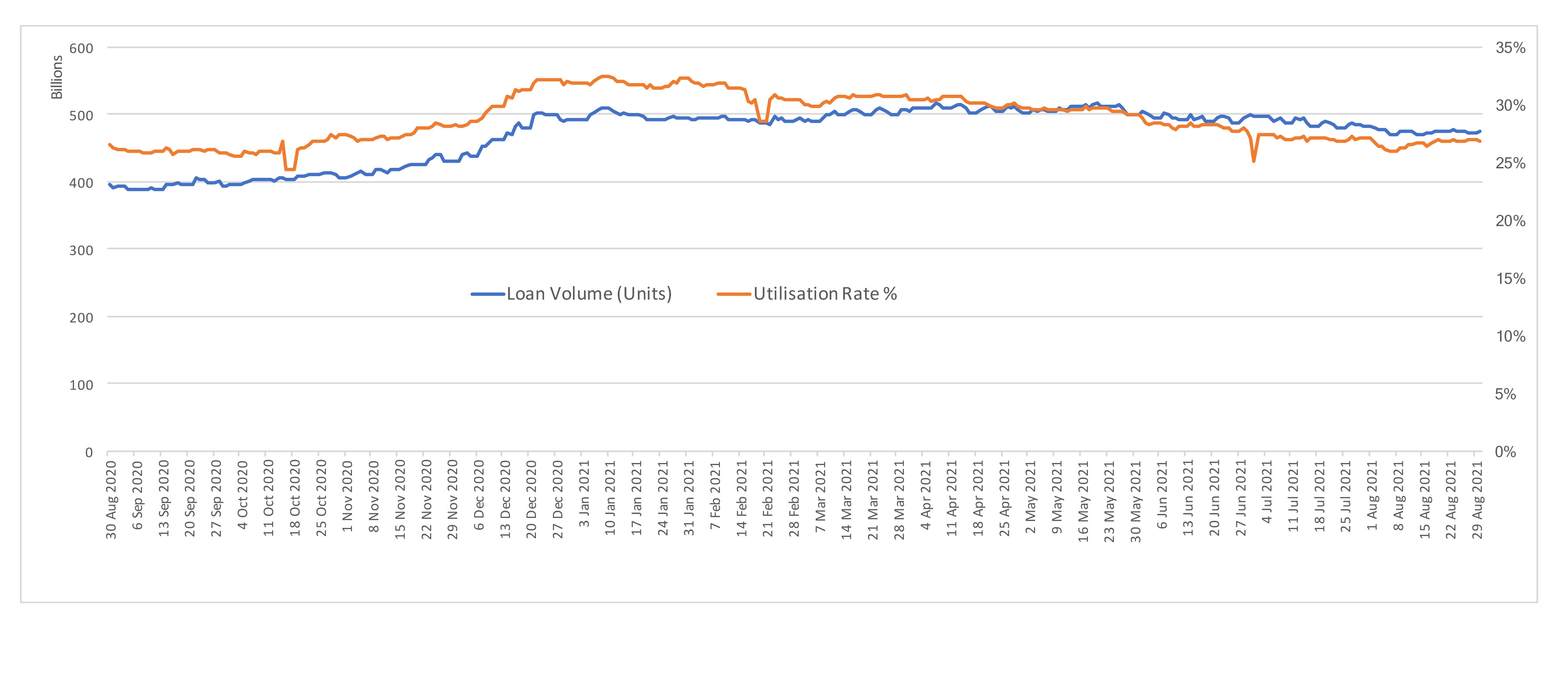

Figure 1 shows that US Treasury lending remains high at over 475 billion bonds (units of treasury, not USD value), which is around 20 per cent higher than 12 months ago but below the 516 billion units seen at the peak which occurred in the first quarter of 2021. Utilisation rose in line with volumes borrowed, but began to narrow in the first quarter of 2021 as volume and demand peaked, falling back to a net rise of just one per cent over the last 12 months, suggesting a significant uptick in lendable supply. With utilisation at less than 30 per cent, this would also suggest that there is a significant amount of untapped US Treasury collateral still available, although some of that is likely to be beyond maturity boundaries and concentration in popular issues may cause localised problems.

Scarcity of collateral will create potential issues across the financial markets way beyond the securities lending and collateral industry. Regulators must be careful when looking to influence the criteria upon which investment funds can invest, provide or receive collateral, but investors and investment managers must also be aware of the effect self-imposed restrictions can bring. Otherwise, we may all end up chasing that one ball around the field which will ruin the game for everyone.

Figure 1